Article

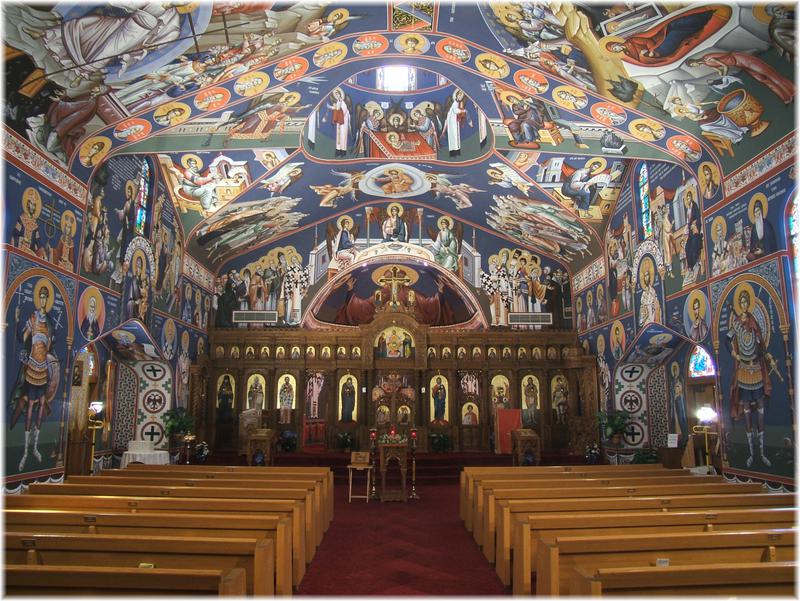

people. Petrovic followed the iconostas from Belgrade to the church in Butte where it was installed. The icon screen depicts the lives of Serbian saints, two saints from the United States involved in the church, Serbian martyrs, the apostles and missionaries for the Slavic people. The pictures, richly painted in Belgrade by Mate Minic, are said to have been written rather than drawn because they tell the stories of the saints’ lives. The iconostas is made of beautiful dark oak and walnut. It is 32 feet long; 20 feet high including an icon cross, and weighs 3.7 tons, a real piece of the “old country”.

The current Serbian Orthodox church, located at 2100 Continental Drive, was the second church in Butte to be funded by the Serbian and Montenegrin community. The first church was built on Idaho Street in 1905 and dedicated on December 16, 1906. The funds were raised from the Serbian and Montenegrin people and functioned not only as a place of worship but also as a gathering place for the Serbian and Montenegrin community.

Roughly sixty years later we built a new church. I asked my father why. He told me that the Anaconda Mining Company was settling with people all over town due to structural damage done to buildings which where collapsing into the mine tunnels underneath them. The Emma Mine and her tunnels were nearly under the church and Father Dosetai, who I remember, feared that the tunnels were fast approaching the danger zone. The Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church negotiated with the Anaconda Mining Company and got the land at 2100 Continental Drive for a new church. They tore down the old church and retained the old land. The lot, which was deteriorating quickly, was eventually deeded to the county, who gave the hallowed ground to a pregnancy center.

For a long time I have been haunted by both the present day life and the long ago past and the way that the two intertwine. It is a past lived by other people so directly connected to me that I am still breathing the remnants of their air. Their blood literally flows in my veins and I forget at times that it is their lives, not my own, that I swoon over.

For a long time I have been haunted by both the present day life and the long ago past and the way that the two intertwine. It is a past lived by other people so directly connected to me that I am still breathing the remnants of their air. Their blood literally flows in my veins and I forget at times that it is their lives, not my own, that I swoon over.

Recently I watched a home video filmed by Silvia and Lou Skuletich. The video shows the Serbian congregation circling the old church on Idaho Street at what seems to be an Easter procession. They stopped at an iron fence near the side doors of the church. I rewound the video and looked twice at those doors. I could have sworn that they were from the present day building, the two buildings overlapping in my mind.

One day, while my mother was in the hospital with her illness, I walked down Idaho Street past the place of the old church. Nothing but an empty lot, landscaped by the pregnancy center, occupied the space. I walked into the middle of that space and I felt the presence of worship, hope, pain, and love, the spirit of the building standing like an ancestral ghost.

The Serbian and Montenegrin people in the Slavic States have had a long history of ghosts, wars, poverty and political upheaval. Even as a young girl I learned of the “Battle of Kosova” in 1389, lost to the Ottoman Turks. All of the Vasovichi clan, of whom my family are direct descendents, over the age of 14 fought in the “Battle of the Blackbirds” at that time. The boys and men all died and the male population had to be restarted from the younger boys.

The Serbian and Montenegrin people in the Slavic States have had a long history of ghosts, wars, poverty and political upheaval. Even as a young girl I learned of the “Battle of Kosova” in 1389, lost to the Ottoman Turks. All of the Vasovichi clan, of whom my family are direct descendents, over the age of 14 fought in the “Battle of the Blackbirds” at that time. The boys and men all died and the male population had to be restarted from the younger boys.

I’ve read Vasko Papa’s poems about the “Battle of the Blackbirds” and about the heads severed by the Turkish armies and displayed on stakes. In his poem Song of the Tower of the Skulls he writes “That’s not our teeth chattering it’s the wind, Idle at the sun’s fair, We grin at you grin up at heaven, What can you do to us, Our skulls are flowering with laughter”. The poem depicts a character of the Montenegrin and Serbian people. Even in death you can’t hurt us. We are strong and full of pride.

I’ve read Vasko Papa’s poems about the “Battle of the Blackbirds” and about the heads severed by the Turkish armies and displayed on stakes. In his poem Song of the Tower of the Skulls he writes “That’s not our teeth chattering it’s the wind, Idle at the sun’s fair, We grin at you grin up at heaven, What can you do to us, Our skulls are flowering with laughter”. The poem depicts a character of the Montenegrin and Serbian people. Even in death you can’t hurt us. We are strong and full of pride.

According to my father, the Ottoman Turks were not the only ones to put the heads of the dead on display. The Montenegrins are said to have cut off the heads of the Turkish soldiers. They also placed them on stakes and lined them up along the border to show the Turkish armies the clear boundary of Montenegro, both a warning and a dare to cross over to the other side.

According to my father, the Ottoman Turks were not the only ones to put the heads of the dead on display. The Montenegrins are said to have cut off the heads of the Turkish soldiers. They also placed them on stakes and lined them up along the border to show the Turkish armies the clear boundary of Montenegro, both a warning and a dare to cross over to the other side.

Defensive or offensive, the Balkan Wars, World War I and World War II, the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo, all took their toll on the Slavic states, each one leaving the region further divided into ethnic groups with little safety outside of a person’s particular ethnic circle. In the early 1900’s Slavic people, who had most often fought over land and religion, left the “old country” and began immigrating to the United States in hopes of gaining some kind of stable ground in both areas.

Defensive or offensive, the Balkan Wars, World War I and World War II, the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo, all took their toll on the Slavic states, each one leaving the region further divided into ethnic groups with little safety outside of a person’s particular ethnic circle. In the early 1900’s Slavic people, who had most often fought over land and religion, left the “old country” and began immigrating to the United States in hopes of gaining some kind of stable ground in both areas.

Although I had never been there I had heard of the “old country” all of my life. Both of my grandparents on my father’s side were immigrants from Montenegro. My grandfather, my jedo, Jedo, and his brother were sent to the seminary to work in 1902. My grandfather, 17 years old, and his brother, Judo, 19 years old, had a different idea. They ran away to Austria and, traveling under the dark cover of night to keep from being captured or killed by marauders, began the trek to America. Somewhere along the way they became separated and lost each other. They eventually reunited in Montana.

Although I had never been there I had heard of the “old country” all of my life. Both of my grandparents on my father’s side were immigrants from Montenegro. My grandfather, my jedo, Jedo, and his brother were sent to the seminary to work in 1902. My grandfather, 17 years old, and his brother, Judo, 19 years old, had a different idea. They ran away to Austria and, traveling under the dark cover of night to keep from being captured or killed by marauders, began the trek to America. Somewhere along the way they became separated and lost each other. They eventually reunited in Montana.

My grandmother on my father’s side is said to have come to the United States when she was two years old. This is a fact I seem to have always known, yet never completely believed. I never once questioned the stories that she told about the “old country”. Her mother could stop a snake with a whistle and had seen the white wolf following her. To save a child’s life her mother had once climbed and crossed a mountain which was haunted by the ghosts of unburied soldiers to bring home a doctor. In my young mind my grandmother, my baba, Baba was raised in Montenegro. Otherwise how could she have known so much about what went on there? It was as if she was able to transcend continents and had one foot in America and one foot in Montenegro.

Other than the few Slavs that arrived at our house for lamb, povetica, apple pita and vichnak every January 7th for our traditional Serbian Christmas celebration I didn’t have a clue how many Serbian and Montenegrin people lived in Butte. Until we became active in the church I naively thought that we were the center of existence for the Serbian and Montenegrin population.

Other than the few Slavs that arrived at our house for lamb, povetica, apple pita and vichnak every January 7th for our traditional Serbian Christmas celebration I didn’t have a clue how many Serbian and Montenegrin people lived in Butte. Until we became active in the church I naively thought that we were the center of existence for the Serbian and Montenegrin population.

In my eleventh year that all changed. In 1965 my three brothers and myself were baptized in the Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church on Continental Drive. People looking and talking like my father and my grandparents came out of the woodwork. They made povetica and drank vichnak. They left their Christmas decorations up until after the Serbian New Year, taking them down near the end of January. They talked about “the old country”, pinched my cheeks and said how much I looked like my baba.

The year that we were baptized was the same year that the new church was completed and the first iconostas for the Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church at 2100 Continental Drive was installed. The first iconostas was supposed to be a temporary structure. It lasted 37 years. The Bishop arrived shortly after our baptisms to bless the new church and the temporary iconostas. I was chosen to present flowers to the visiting Bishop on that day. I proudly wore a white dress that my Scottish maternal grandmother, Nana, helped me make.

The year that we were baptized was the same year that the new church was completed and the first iconostas for the Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church at 2100 Continental Drive was installed. The first iconostas was supposed to be a temporary structure. It lasted 37 years. The Bishop arrived shortly after our baptisms to bless the new church and the temporary iconostas. I was chosen to present flowers to the visiting Bishop on that day. I proudly wore a white dress that my Scottish maternal grandmother, Nana, helped me make.

The home video filmed by Silvia and Lou Skuletich, which follows the building of the new church, shows not only the grounds’ blessing and the first shovel of dirt dug up, but also my presentation of flowers to the Bishop. There he is, entering the church, the heavy wooden doors open, his back to the camera, his black robe flowing and one lone flower waving over his shoulder. You can’t see me beyond his great presence, but I am there, standing right in front of him, with my black hair cut short, my cat-eye glasses pointing toward the balcony, and my scrawny 11 year old arms raised in offering.

The home video filmed by Silvia and Lou Skuletich, which follows the building of the new church, shows not only the grounds’ blessing and the first shovel of dirt dug up, but also my presentation of flowers to the Bishop. There he is, entering the church, the heavy wooden doors open, his back to the camera, his black robe flowing and one lone flower waving over his shoulder. You can’t see me beyond his great presence, but I am there, standing right in front of him, with my black hair cut short, my cat-eye glasses pointing toward the balcony, and my scrawny 11 year old arms raised in offering.

After we were baptized we regularly attended liturgy on Sundays. I loved the choir and the way the priest’s voice sang out in Church Slavonic. I made up my own idea of what was being said in the service since I didn’t speak Serbian. Today most of the service is in English yet the choir still sings some of the responses in Serbian. I often sing along, having absorbed parts of the language.

In those days I could only hope to learn some of the Serbian language from church, since Jedo, my grandfather, had forbidden his family to speak anything but English, insisting that they needed to learn the language of their new country. Still, some words slipped in during church or later during coffee hour in the Parish Hall. I learned words like “crce moya”, sweetheart, “Crnogorski”, Montenegrin, and “hvala”, thank you.

In those days I could only hope to learn some of the Serbian language from church, since Jedo, my grandfather, had forbidden his family to speak anything but English, insisting that they needed to learn the language of their new country. Still, some words slipped in during church or later during coffee hour in the Parish Hall. I learned words like “crce moya”, sweetheart, “Crnogorski”, Montenegrin, and “hvala”, thank you.

I learned to make povetica, to burn the yule log for Serbian Christmas Eve to stand guard over Christ’s tomb on Holy Friday, the Friday night before Easter, Serbian Easter. I attended dinners put on by the Circle of Serbian Sisters and helped my dad tend bar at “A Night in Yugoslavia”. I gained an early affection for Baba’s scarves, which I tied wildly in my hair.

I learned to make povetica, to burn the yule log for Serbian Christmas Eve to stand guard over Christ’s tomb on Holy Friday, the Friday night before Easter, Serbian Easter. I attended dinners put on by the Circle of Serbian Sisters and helped my dad tend bar at “A Night in Yugoslavia”. I gained an early affection for Baba’s scarves, which I tied wildly in my hair.

When I couldn’t believe in myself, which was often in those early days, I could always believe in my Montenegrin ancestry. I’d heard the stories of the Montenegrin soldiers who fought bare-footed and in rags. Their spirit was filled with black powder. I grew up a brave, proud Montenegrin warrior in Butte, Montana. I didn’t need to be a person in my own right with the strength of such great ancestors behind me.

Nearly thirty-five years after my baptism, two days before my mother died, I dreamed that I stood with my ancestors at the edge of a sharp canyon above a great river in Montenegro. Some of the men were setting up a two-way radio so that we could communicate with the other side. There was a composer there from the other side who understood music and the nature of this kind of communication. When the job was completed the ancestors floated back over to the other side of the river.

Nearly thirty-five years after my baptism, two days before my mother died, I dreamed that I stood with my ancestors at the edge of a sharp canyon above a great river in Montenegro. Some of the men were setting up a two-way radio so that we could communicate with the other side. There was a composer there from the other side who understood music and the nature of this kind of communication. When the job was completed the ancestors floated back over to the other side of the river.

I woke up that January morning and sat with my mother who, being very weak and in and out of various forms of alertness, seemed to have a foot in two worlds. She said that it was so wonderful to be in touch with Mark again, my brother who had died twenty years earlier and that Nana, my Scottish grandmother who had died that fall, looked great. Somewhere in the middle of the day, while Mom slept, before I told anyone about the dream, my father revealed another piece of information to me about my ancestors. Baba had an uncle who was considered to have been a great composer.

I woke up that January morning and sat with my mother who, being very weak and in and out of various forms of alertness, seemed to have a foot in two worlds. She said that it was so wonderful to be in touch with Mark again, my brother who had died twenty years earlier and that Nana, my Scottish grandmother who had died that fall, looked great. Somewhere in the middle of the day, while Mom slept, before I told anyone about the dream, my father revealed another piece of information to me about my ancestors. Baba had an uncle who was considered to have been a great composer.

Later that night, before Mom went into a coma, my father sat with her and sang while she rested. For several days after she died I seemed to have a two-way radio to the other side, the strength of my Slavic ancestors helping me with my mother’s passing.

One year, just before Christmas, I met a Serbian woman my father’s age in Polson at the Episcopalian Church who knew my grandparents and again the stories started. “You look just like Josie,” said Sue Trbovich Williamson, calling my grandmother by her Americanized name. I had rarely heard her called “Josie”. Her name was Jovanka, changed to Yvonne on her naturalization certificate and changed further yet to Josie by her American friends.

One year, just before Christmas, I met a Serbian woman my father’s age in Polson at the Episcopalian Church who knew my grandparents and again the stories started. “You look just like Josie,” said Sue Trbovich Williamson, calling my grandmother by her Americanized name. I had rarely heard her called “Josie”. Her name was Jovanka, changed to Yvonne on her naturalization certificate and changed further yet to Josie by her American friends.

That Christmas, American Christmas, the Christmas the rest of the Christian world celebrates, I was in Butte with my father and I wanted to go to church. But that Christmas fell on a Wednesday and so the Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church had no service. I asked my dad if he’d like to go to St. Anne’s, one of Butte’s Catholic churches, for midnight service. He said that he was tired and midnight service was too late for him.

That Christmas, American Christmas, the Christmas the rest of the Christian world celebrates, I was in Butte with my father and I wanted to go to church. But that Christmas fell on a Wednesday and so the Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Church had no service. I asked my dad if he’d like to go to St. Anne’s, one of Butte’s Catholic churches, for midnight service. He said that he was tired and midnight service was too late for him.

The next morning I had decided I’d go to church by myself and before I could tell him where I was going he asked me if I’d like to go to the Episcopalian church for the Christmas morning service. He said that he knew a priest there who sometimes came to the Orthodox Church. Even though it’s unlikely that he would have seen it this way, I knew that he had just made a very generous offering. I hadn’t expected my Montenegrin, Orthodox father to attend another service on the Christmas day that was not a Serbian Christmas day.

The next morning I had decided I’d go to church by myself and before I could tell him where I was going he asked me if I’d like to go to the Episcopalian church for the Christmas morning service. He said that he knew a priest there who sometimes came to the Orthodox Church. Even though it’s unlikely that he would have seen it this way, I knew that he had just made a very generous offering. I hadn’t expected my Montenegrin, Orthodox father to attend another service on the Christmas day that was not a Serbian Christmas day.

Once inside of the beautiful stone structure my father told me that sometimes, when the Orthodox Church didn’t have services, his mother attended this church. That sent me into tears, to be sitting in a church I’d never been in and to know that forty years earlier, my grandmother may have been sitting there in the same pew, the ghost of my ancestry ever at my side.

During the war in Kosova, Father Bratislav preached peace and looked worn and concerned. His family lived in Bosnia at the time. They later moved to the Republic of Serbska. Shortly after the war ended, Svjetlan, and his brother’s wife, Nedeljka, came to live in Butte. At That time they spoke only Serbian and were slowly learning English. They were Butte’s most recent Slavic immigrants.

During the war in Kosova, Father Bratislav preached peace and looked worn and concerned. His family lived in Bosnia at the time. They later moved to the Republic of Serbska. Shortly after the war ended, Svjetlan, and his brother’s wife, Nedeljka, came to live in Butte. At That time they spoke only Serbian and were slowly learning English. They were Butte’s most recent Slavic immigrants.

After church on Bright Monday, the Monday after Serbian Easter, I spoke with Svjetlan. He was 34 years old. The war in Kosova ended in 1999, when he was 29. In broken English he said that he could explain it very well what happened.

After church on Bright Monday, the Monday after Serbian Easter, I spoke with Svjetlan. He was 34 years old. The war in Kosova ended in 1999, when he was 29. In broken English he said that he could explain it very well what happened.

He said that “how do you call it? You know. Killing people?”

He said that “how do you call it? You know. Killing people?”

“War?” I offered.

“War?” I offered.

“Yes, war. War destroyed a lot of buildings, killed a lot of people. Politically it is very bad. My family, my parents and my brother, live in Republic of Serbska. You know it? Republic of Serbska?”

“Yes, war. War destroyed a lot of buildings, killed a lot of people. Politically it is very bad. My family, my parents and my brother, live in Republic of Serbska. You know it? Republic of Serbska?”

“Yes.” Well, I did, but very, very vaguely.

“Yes.” Well, I did, but very, very vaguely.

“Republic of Serbska is the safe place for Serbs. Politically it is very bad. So we come here.”

“Republic of Serbska is the safe place for Serbs. Politically it is very bad. So we come here.”

“Will you stay here?” I wanted somehow to welcome him, yet I’d become acutely aware that no matter how much I had claimed my “homeland” and my warrior status in my stories, my language and my dreams, I have never lived through a war. The shallowness of my life came crashing down on me and all I wanted was to offer him something, one thing, for the suffering he had done for my, our, his, all people.

“Will you stay here?” I wanted somehow to welcome him, yet I’d become acutely aware that no matter how much I had claimed my “homeland” and my warrior status in my stories, my language and my dreams, I have never lived through a war. The shallowness of my life came crashing down on me and all I wanted was to offer him something, one thing, for the suffering he had done for my, our, his, all people.

“Yes. If we can work. I can’t talk so well, but, maybe, hopefully, soon,” he said.

“Yes. If we can work. I can’t talk so well, but, maybe, hopefully, soon,” he said.

“I think you are speaking really well,” I said, realizing that all I had to offer was kindness. “We are glad you’re here.”

“I think you are speaking really well,” I said, realizing that all I had to offer was kindness. “We are glad you’re here.”

Like the immigration of Svjetlan and Nedeljka Krsic the first Slavic immigration to America was spurred on by War, the Balkan Wars, World War I, economic crisis and political upheaval. The Serbs and Montenegrins in those days would have very likely said that a lot of buildings were ruined, a lot of people were killed, and that politically things were very bad. They had a hope for a new chance in America, a hope to make a decent living and to see their sons and daughters live a natural life span.

Like the immigration of Svjetlan and Nedeljka Krsic the first Slavic immigration to America was spurred on by War, the Balkan Wars, World War I, economic crisis and political upheaval. The Serbs and Montenegrins in those days would have very likely said that a lot of buildings were ruined, a lot of people were killed, and that politically things were very bad. They had a hope for a new chance in America, a hope to make a decent living and to see their sons and daughters live a natural life span.

Serbs and Montenegrins arrived in Butte in the early 1900’s looking for employment opportunities, which the mines offered. In fact, an entire chapter of Copper Camp by the Writer’s Project of Montana is dedicated to the Serbian population arriving in Butte. According to Copper Camp, the Serbian and Montenegrin population worked hard and others felt that their jobs were threatened by the multitudes that flooded the mining town looking for work.

Serbs and Montenegrins arrived in Butte in the early 1900’s looking for employment opportunities, which the mines offered. In fact, an entire chapter of Copper Camp by the Writer’s Project of Montana is dedicated to the Serbian population arriving in Butte. According to Copper Camp, the Serbian and Montenegrin population worked hard and others felt that their jobs were threatened by the multitudes that flooded the mining town looking for work.

Growing up I thought of “Serbian/Montenegrin” as a good thing. When I was young we clumped them together like that. “You’re Serbian, Crnogorski, Montenegrin.” And I was proud to be a “Serbian, Crnogorski, Montenegrin.” It shaped my identity.

Growing up I thought of “Serbian/Montenegrin” as a good thing. When I was young we clumped them together like that. “You’re Serbian, Crnogorski, Montenegrin.” And I was proud to be a “Serbian, Crnogorski, Montenegrin.” It shaped my identity.

I saw all Serbs, Montenegrins and, yes, Croatians as family. When I first met Michael Patterson, a young Croatian man, in my university Russian class in 1973 we became immediate friends and started exchanging the Serbo-Croatian words that we knew. Imagine my surprise many years later during the war in Bosnia to find myself in a barroom fight with a man who had friends in Croatia. It went something like this:

I saw all Serbs, Montenegrins and, yes, Croatians as family. When I first met Michael Patterson, a young Croatian man, in my university Russian class in 1973 we became immediate friends and started exchanging the Serbo-Croatian words that we knew. Imagine my surprise many years later during the war in Bosnia to find myself in a barroom fight with a man who had friends in Croatia. It went something like this:

“Milosavich is an evil son-of-a-bitch.” Him.

“Milosavich is an evil son-of-a-bitch.” Him.

“I agree.” Me.

“I agree.” Me.

“Serbs are assholes.” Him.

“Serbs are assholes.” Him.

“Not all Serbs.” Me.

“Not all Serbs.” Me.

“They are slaughtering people and barely even burying them. They’re evil.” Him.

“They are slaughtering people and barely even burying them. They’re evil.” Him.

“I know. It’s wrong.” Me.

“I know. It’s wrong.” Me.

“You guys ought to be shot.” Him. Yelling.

“You guys ought to be shot.” Him. Yelling.

“Well, this war doesn’t come out of nowhere.” Me. Doubling up my fist.

“Well, this war doesn’t come out of nowhere.” Me. Doubling up my fist.

“My friends are there. You people are killing my friends.” Him. Spitting.

“My friends are there. You people are killing my friends.” Him. Spitting.

“I’m not saying its right, but the Croatians aren’t all innocent.” Me.

“I’m not saying its right, but the Croatians aren’t all innocent.” Me.

“Milosavich is an evil bastard and so are the Serbs.” Him.

“Milosavich is an evil bastard and so are the Serbs.” Him.

“The Ustachis buried hundreds of people alive.” Me. Doubling both fists.

“The Ustachis buried hundreds of people alive.” Me. Doubling both fists.

“In 1945? You Serbs are bastards.” Him. Towering over me.

“In 1945? You Serbs are bastards.” Him. Towering over me.

“You’re a bastard.” Me. Ready to fly into him.

“You’re a bastard.” Me. Ready to fly into him.

“Let’s go.” My friend. Taking my arm and dragging me out of there.

“Let’s go.” My friend. Taking my arm and dragging me out of there.

That was it right there: a microsm of the war.

That was it right there: a microsm of the war.

Later that season a friend called to invite me to a party. “There will be a person from France and a German person and a Belgian person there. And a Serb if you come. That is if you still claim being Serbian.” No. I stopped claiming myself when the war began. I don’t exist anymore. “No thanks, I’m busy that evening.” I was furious. I’m “Serbian, Crnogorski, Montenegrin.” I fight barefooted and in rags. My spirit is filled with black powder.

Fortunately, other people understood the war and the Serbian, the Montenegrin, and the Croatian people differently. Mary Herak Sand, a counselor in Polson, where I lived during the war in Bosnia, called me up to welcome me to the community. It turned out that she is of Croatian and Irish descent. We, quite naturally and quite hesitantly, if you can do both at the same time, began to talk about our histories, our people, our food, our families and, yes, our war. We both ended up crying and apologizing. We cried for something that, while happening on another continent, haunted both of us. And, miracle of miracles, here it was: a microsm of the solution.

Fortunately, other people understood the war and the Serbian, the Montenegrin, and the Croatian people differently. Mary Herak Sand, a counselor in Polson, where I lived during the war in Bosnia, called me up to welcome me to the community. It turned out that she is of Croatian and Irish descent. We, quite naturally and quite hesitantly, if you can do both at the same time, began to talk about our histories, our people, our food, our families and, yes, our war. We both ended up crying and apologizing. We cried for something that, while happening on another continent, haunted both of us. And, miracle of miracles, here it was: a microsm of the solution.

Boundaries had been crossed and in a small part of the world, far away from Bosnia, a Serb and a Croatian held hands. We had lived with, wrestled with, and loved the ghosts of our ancestors all of our lives. We understood each other and we wanted the war to end.

My own ancestral ghost and its arrival in America began long before I was born. By 1911 both of my grandparents had finally arrived in America from Montenegro. The story I remember is that my grandmother, Baba, was a baby and my grandfather, Jedo, was 20 and he carried her off of the boat. Both families went to Butte. Years later, when Baba was 15 and her parents both died, she needed someone to take care of her and her younger brother. Jedo was a gambler and the families thought that he was too wild. They thought that a family would help to settle him down. The families put Baba and Jedo in a room to discuss marriage.

“Do you want to get married, Jovanka?” My grandfather asked.

“Do you want to get married, Jovanka?” My grandfather asked.

“I don’t care, Milosav. Do you?” My grandmother returned.

“I don’t care, Milosav. Do you?” My grandmother returned.

“Well, if you want to,” Jedo said.

“Well, if you want to,” Jedo said.

“OK. If you want to,” Baba answered. And that was that.

“OK. If you want to,” Baba answered. And that was that.

Except that this isn’t the absolute truth of the story anymore. A few years before my uncle died he told me a more elaborate story of my grandparents’ wedding arrangement. And after reading the naturalization certificates of both of my grandparents and their wedding certificate I realize that my grandmother’s parents hadn’t died by the time they got married. This cracked the firm hold I had on my ancestral roots. I went to my father and asked “now, how did it all happen again?”

Except that this isn’t the absolute truth of the story anymore. A few years before my uncle died he told me a more elaborate story of my grandparents’ wedding arrangement. And after reading the naturalization certificates of both of my grandparents and their wedding certificate I realize that my grandmother’s parents hadn’t died by the time they got married. This cracked the firm hold I had on my ancestral roots. I went to my father and asked “now, how did it all happen again?”

And, I guess that now the truth is that my grandfather arrived in America somewhere around 1907 and was held up in Chicago for several months gambling before he ever got to Montana. He wired his brother, Judo, for money so he could join him in Taft, Montana to work on the railroad. His brother sent money. My grandfather gambled it away. His brother sent a train ticket. My grandfather cashed the train ticket in for money and gambled it away. His brother sent the conductor with the train ticket who never let my grandfather touch it. Finally, my grandfather arrived in Taft. And as it turns out--and both my uncle and my father agree on this--Jedo actually carried Baba off of the train, not the boat.

And, I guess that now the truth is that my grandfather arrived in America somewhere around 1907 and was held up in Chicago for several months gambling before he ever got to Montana. He wired his brother, Judo, for money so he could join him in Taft, Montana to work on the railroad. His brother sent money. My grandfather gambled it away. His brother sent a train ticket. My grandfather cashed the train ticket in for money and gambled it away. His brother sent the conductor with the train ticket who never let my grandfather touch it. Finally, my grandfather arrived in Taft. And as it turns out--and both my uncle and my father agree on this--Jedo actually carried Baba off of the train, not the boat.

There is another crack in the story. Recently I looked at both Jedo’s naturalization certificate from 1917 and their marriage certificate from 1924. He is listed as 32 years old on both certificates. My father says that Jedo never cared about age until it came time for him to collect social security. At that time, without the papers to prove his age, he said, “All they have to do is go look at the date on Judo’s tombstone. Every one knows that he was two years older than me.”

There is another crack in the story. Recently I looked at both Jedo’s naturalization certificate from 1917 and their marriage certificate from 1924. He is listed as 32 years old on both certificates. My father says that Jedo never cared about age until it came time for him to collect social security. At that time, without the papers to prove his age, he said, “All they have to do is go look at the date on Judo’s tombstone. Every one knows that he was two years older than me.”

When Jedo finally made it to Montana, in 1907, he and his brother, Judo, were in Taft to work on the railroad. The night that Jedo arrived in Taft they witnessed an Irishman kill a Montenegrin. The Irishman evidently saw that they had seen the murder and came after them. They barricaded themselves into their hotel room with the hotel furniture. Judo knew enough English to bluff the man and tell him that they had a gun. The man said that he didn’t know if they did or not but that they had better be gone by the next day. They didn’t stop to collect their wages. They simply left and never turned back. Jedo told my father that Taft was the most dangerous town in Montana, that a man was killed nearly every day there and he was glad to have left.

When Jedo finally made it to Montana, in 1907, he and his brother, Judo, were in Taft to work on the railroad. The night that Jedo arrived in Taft they witnessed an Irishman kill a Montenegrin. The Irishman evidently saw that they had seen the murder and came after them. They barricaded themselves into their hotel room with the hotel furniture. Judo knew enough English to bluff the man and tell him that they had a gun. The man said that he didn’t know if they did or not but that they had better be gone by the next day. They didn’t stop to collect their wages. They simply left and never turned back. Jedo told my father that Taft was the most dangerous town in Montana, that a man was killed nearly every day there and he was glad to have left.

This story also appears in Edith Schussler’s book, Doctors, Dynamite and Dogs. Although the book is about her and Dr. Schussler’s life in Taft she dedicates an entire chapter to the event. She says that the Montenegrin man who was killed was “the king” and that all of the Montenegrin men admired him. He helped them by talking for them and managing their money.

This story also appears in Edith Schussler’s book, Doctors, Dynamite and Dogs. Although the book is about her and Dr. Schussler’s life in Taft she dedicates an entire chapter to the event. She says that the Montenegrin man who was killed was “the king” and that all of the Montenegrin men admired him. He helped them by talking for them and managing their money.

She writes that in 1907 “Reddy Hayes, foreman of the tunnel camp, appeared on the brow of Hospital Hill. Striding rapidly toward us, he called out, ‘Doc, I killed the Mountain Nigger King. I’m on my way to Missoula to give myself up. There’ll be hell to pay here. They say that they will burn the camp and blow up the hospital. It’ll be hell here, alright”.

She writes that in 1907 “Reddy Hayes, foreman of the tunnel camp, appeared on the brow of Hospital Hill. Striding rapidly toward us, he called out, ‘Doc, I killed the Mountain Nigger King. I’m on my way to Missoula to give myself up. There’ll be hell to pay here. They say that they will burn the camp and blow up the hospital. It’ll be hell here, alright”.

She goes on to relay Reddy’s story that “the king had refused to obey orders” and had become surly and then pulled a gun on him but Reddy beat the king to it. She tells an elaborate story of the town’s fear of the Montenegrin men, the funeral, and the disappearance of all of the Montenegrin men from Taft after the funeral.

Reddy was acquitted in self-defense and stayed away for several months until he figured the trouble had blown over. When he returned, Edith and the doctor advised him to leave again. He didn’t. He said all of the Montenegrins had left Taft and that he would be fine. Within the hour Edith Schussler heard shots ring out. Reddy was dead, along with five Montenegrin men. She ends the chapter suggesting that if only they had taken the time to understand one another such a thing would have never happened.

I am second generation American. I have eight godchildren. In the Orthodox tradition I am responsible for the development of their souls. I tell stories about their grandparents, their great grandparents and their great-great grandparents. They ask questions and they remember. They say things like “I’m like Baba. Tough.” Now, when they say “Baba” they don’t actually mean my Baba. They mean my mother, their grandmother or great grandmother, who was actually Scotch-Irish, without a Slavic cell in her body.

My mother converted to the Serbian Orthodox religion. She spoke as many Serbian words as myself and taught me to make povetica. Her funeral was held in the Orthodox Church and she is buried, not next to her mother, Nana, my full-blooded Scottish grandmother, or her father, Pabum, my full-blooded Irish grandfather, but rather, in the Montenegrin and Serbian section of the Mountain View Cemetery in Butte. Her grave is in front of my youngest brother’s, Mark, and his son’s, Daniel, and his grandson’s, Jeremy. Her grave is next to my father’s, who has since passed on, in front of my grandmother’s, Baba, next to my dad’s brother, Uncle Bob, across the road from my grandfather’s, Jedo, and his brother, Judo, and my dad’s sister, Milosava, just down the road from my dad’s other sister, Stana.

My mother converted to the Serbian Orthodox religion. She spoke as many Serbian words as myself and taught me to make povetica. Her funeral was held in the Orthodox Church and she is buried, not next to her mother, Nana, my full-blooded Scottish grandmother, or her father, Pabum, my full-blooded Irish grandfather, but rather, in the Montenegrin and Serbian section of the Mountain View Cemetery in Butte. Her grave is in front of my youngest brother’s, Mark, and his son’s, Daniel, and his grandson’s, Jeremy. Her grave is next to my father’s, who has since passed on, in front of my grandmother’s, Baba, next to my dad’s brother, Uncle Bob, across the road from my grandfather’s, Jedo, and his brother, Judo, and my dad’s sister, Milosava, just down the road from my dad’s other sister, Stana.

One day, shortly after my mother passed away, my father and I were at the cemetery visiting her grave. Although he might not have said this, I believe that he and I were alike in that we had grown used to the ghosts and we no longer felt haunted by their presence, only blessed. After placing the flowers on my mother’s grave we walked over and talked to a white haired Zorka Milanovich, who was leaning on her husband’s tombstone. She was kind and sweet and seemed to be using the stone to hold herself up. She mentioned the “old country”.

Walking back to the car my dad commented on how good she looked. She had just had a birthday. The way that I remember it she was one hundred and one years old, although he said that she was only ninety or so. Later that week she died and I felt sad about seeing her there so brightly one day and her being gone from us a few days later. I wondered if she had finally crossed the river to our ancestors and made it back to the “old country”. I wondered who would be waiting for her there. The Montenegrins, the Serbs, the Croatians, the Scotch, the Irish, the Turks. Somehow, I think they might all be standing together on the other side, with their two-way radios, singing the songs of the dead, as if they were their own nation.

Walking back to the car my dad commented on how good she looked. She had just had a birthday. The way that I remember it she was one hundred and one years old, although he said that she was only ninety or so. Later that week she died and I felt sad about seeing her there so brightly one day and her being gone from us a few days later. I wondered if she had finally crossed the river to our ancestors and made it back to the “old country”. I wondered who would be waiting for her there. The Montenegrins, the Serbs, the Croatians, the Scotch, the Irish, the Turks. Somehow, I think they might all be standing together on the other side, with their two-way radios, singing the songs of the dead, as if they were their own nation.