© Moronic Ox Literary Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books

Moronic Ox Literary and Cultural Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books Advertise your book, CD, or cause in the 'Ox'

Novel Excerpts, Short Stories, Poetry, Multimedia, Current Affairs, Book Reviews, Photo Essays, Visual Arts Submissions

"Monster Movies: A Personal Remembrance"

by David Gariff

“For one who has not lived even a single lifetime, you are a wise man, Van Helsing.”

“

The way you walked was thorny, through no fault of your own. But as the rain enters the soil, the river enters the sea, so tears run to a predestined end. Your suffering is over. Now you will find peace for eternity.”

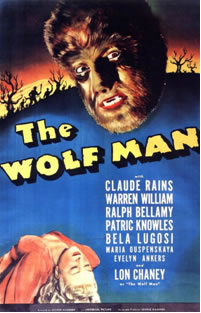

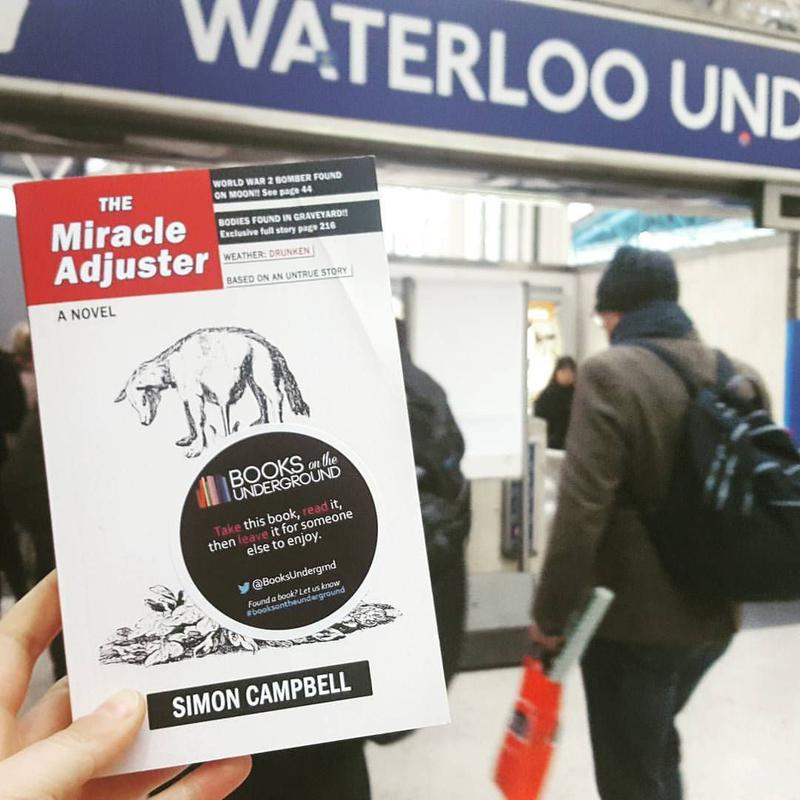

Maleva the gypsy speaks these words of comfort and redemption over the body of the slain Wolfman as he reassumes his human form of Larry Talbot. Lon Chaney Jr. portrays Talbot who, having earlier saved a young woman from an attack by a wolf, was himself bitten, thus beginning his slow and agonizing descent into terror.

Maleva the gypsy speaks these words of comfort and redemption over the body of the slain Wolfman as he reassumes his human form of Larry Talbot. Lon Chaney Jr. portrays Talbot who, having earlier saved a young woman from an attack by a wolf, was himself bitten, thus beginning his slow and agonizing descent into terror.

“Even the man who’s pure of heart and says his prayers at night / May become a wolf when the wolf bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.”

Chaney’s performance is worthy of his illustrious father, not because of any tricks of make-up, but due to the pathos of his facial expressions and body language. Chaney makes palpable the panic about his descent into this recurring madness. His dread speaks to our deeper instincts and reminds us of the thin line between our capacity for good and our darker fears.

Chaney’s performance is worthy of his illustrious father, not because of any tricks of make-up, but due to the pathos of his facial expressions and body language. Chaney makes palpable the panic about his descent into this recurring madness. His dread speaks to our deeper instincts and reminds us of the thin line between our capacity for good and our darker fears.

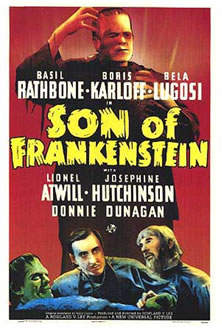

No portrayal of the tormented soul is better than Boris Karloff’s interpretation of the Frankenstein monster. Assuming a role originally destined for Bela Lugosi after his success in Dracula, Karloff transformed the mute character into a tour de force of expressive acting. Hearkening back to the tradition of German Expressionism, the original inspiration for all the Universal horror pictures, and exploiting the make-up designs of Jack Pierce, reminiscent of the heavy, white, cake make-up of the expressionist tradition, Karloff manages to create a moving portrait of psychological and emotional range and depth.

No portrayal of the tormented soul is better than Boris Karloff’s interpretation of the Frankenstein monster. Assuming a role originally destined for Bela Lugosi after his success in Dracula, Karloff transformed the mute character into a tour de force of expressive acting. Hearkening back to the tradition of German Expressionism, the original inspiration for all the Universal horror pictures, and exploiting the make-up designs of Jack Pierce, reminiscent of the heavy, white, cake make-up of the expressionist tradition, Karloff manages to create a moving portrait of psychological and emotional range and depth.

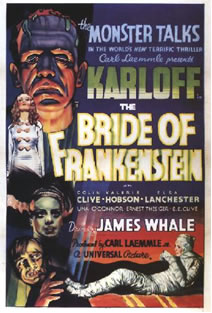

Of singular importance in the best of the Universal horror pictures was the supporting cast of actors, often appearing in more than one film. The list is impressive and includes such notables as Basil Rathbone, Claude Rains, Elsa Lanchester, Colin Clive, Evelyn Ankers, and Ralph Bellamy supplemented by a remarkable array of character actors and unique and eccentric personalities, among them: Edward Van Sloan, Dwight Frye, Maria Ouspenskaya, and Una O’Connor. Here again, it wasn’t the portrayals by the more famous actors in the films that resonated with me but the “types” conveyed through the character roles. Each “type” represented a specific societal archetype or psychic state. Dwight Frye as Renfield/Fritz/Karl (in various films) – the dedicated, abused, child-like lab assistant, slightly deranged but loyal; Maria Ouspenskaya as Maleva – gypsy, mother, protectress, and guardian of occult secrets; Una O’Connor – comedic relief and a pure portrait of what it meant to be frightened by the mere mention of ghosts and monsters. Finally, there was Edward Van Sloan.

Of singular importance in the best of the Universal horror pictures was the supporting cast of actors, often appearing in more than one film. The list is impressive and includes such notables as Basil Rathbone, Claude Rains, Elsa Lanchester, Colin Clive, Evelyn Ankers, and Ralph Bellamy supplemented by a remarkable array of character actors and unique and eccentric personalities, among them: Edward Van Sloan, Dwight Frye, Maria Ouspenskaya, and Una O’Connor. Here again, it wasn’t the portrayals by the more famous actors in the films that resonated with me but the “types” conveyed through the character roles. Each “type” represented a specific societal archetype or psychic state. Dwight Frye as Renfield/Fritz/Karl (in various films) – the dedicated, abused, child-like lab assistant, slightly deranged but loyal; Maria Ouspenskaya as Maleva – gypsy, mother, protectress, and guardian of occult secrets; Una O’Connor – comedic relief and a pure portrait of what it meant to be frightened by the mere mention of ghosts and monsters. Finally, there was Edward Van Sloan.

The Van Sloan characters (he too appeared in multiple films), acting as father/teacher/mentor and guide, were called upon to solve the mysteries. As Dr. Van Helsing in Dracula, Edward Van Sloan encouraged me to pursue a life of learning. There he stood: educated, understated, slightly awkward, a man of books. Rational and worldly, he yet knew that some things cannot be explained by logic and reason alone. Van Helsing approaches his encounter with the Count coolly, unafraid of his adversary’s powers -- of which only he knows the full extent -- stands toe to toe with the danger, and ultimately is victorious. When Count Dracula compliments the professor with the statement with which this essay begins, it was always a personal triumph for me. Van Helsing demonstrated to a young boy from Rochester that knowledge is power. From this late night monster movie I came away with one of my most cherished and firmly held beliefs in life.

The Van Sloan characters (he too appeared in multiple films), acting as father/teacher/mentor and guide, were called upon to solve the mysteries. As Dr. Van Helsing in Dracula, Edward Van Sloan encouraged me to pursue a life of learning. There he stood: educated, understated, slightly awkward, a man of books. Rational and worldly, he yet knew that some things cannot be explained by logic and reason alone. Van Helsing approaches his encounter with the Count coolly, unafraid of his adversary’s powers -- of which only he knows the full extent -- stands toe to toe with the danger, and ultimately is victorious. When Count Dracula compliments the professor with the statement with which this essay begins, it was always a personal triumph for me. Van Helsing demonstrated to a young boy from Rochester that knowledge is power. From this late night monster movie I came away with one of my most cherished and firmly held beliefs in life.

As a youngster, I had no knowledge of any of these actors, directors, and technical artists. My involvement with the films was personal and hermetic. Initially I had not even read Bram Stoker or Mary Shelley. Late Saturday night, while everyone else in my house was sleeping, I would sit alone in front of the television, transported from Rochester to the locales portrayed in the films from England to Egypt to Transylvania and beyond.

As a youngster, I had no knowledge of any of these actors, directors, and technical artists. My involvement with the films was personal and hermetic. Initially I had not even read Bram Stoker or Mary Shelley. Late Saturday night, while everyone else in my house was sleeping, I would sit alone in front of the television, transported from Rochester to the locales portrayed in the films from England to Egypt to Transylvania and beyond.

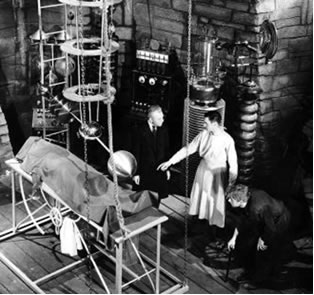

It was the look of the Universal films more than anything that first made an impression on me. Dracula’s ruined Carfax Abbey, the futuristic lab of Dr. Frankenstein with its fantastic electrical equipment, crosses in graveyards silhouetted against a moonlit sky, the ever-present evening fog lying low along the ground, a network of tree limbs threatening in the breeze, and the moors -- always the moors. Not exactly sure what a moor was, I nevertheless knew it was dangerous to walk it alone at night. In addition, there was the illumination of the scenes, a never-ending array of lights and darks creating velvety textures one moment and sharp edges the next. It was a black and white world of high contrasts and low contrasts both real and strangely artificial, but perfect for the stories being told.

It was the look of the Universal films more than anything that first made an impression on me. Dracula’s ruined Carfax Abbey, the futuristic lab of Dr. Frankenstein with its fantastic electrical equipment, crosses in graveyards silhouetted against a moonlit sky, the ever-present evening fog lying low along the ground, a network of tree limbs threatening in the breeze, and the moors -- always the moors. Not exactly sure what a moor was, I nevertheless knew it was dangerous to walk it alone at night. In addition, there was the illumination of the scenes, a never-ending array of lights and darks creating velvety textures one moment and sharp edges the next. It was a black and white world of high contrasts and low contrasts both real and strangely artificial, but perfect for the stories being told.

It was with these Universal horror films that I first learned about the power of the visual image. I am certain this occurred before my involvement with painting and the history of art but contemporary with my introduction to classical music (Beethoven) and opera. Later, as a student of art and film history I discovered the many debts owed by these Universal pictures to European traditions of art, music, literature, folklore, and filmmaking.

It was with these Universal horror films that I first learned about the power of the visual image. I am certain this occurred before my involvement with painting and the history of art but contemporary with my introduction to classical music (Beethoven) and opera. Later, as a student of art and film history I discovered the many debts owed by these Universal pictures to European traditions of art, music, literature, folklore, and filmmaking.

There are those who criticize the plots, character development, dialogue, and acting in these 1930s’ movies. Yet it is the power of the visual images that captured me as an adolescent viewer and has stayed with me today as a more sophisticated and image-conscious art historian. This new visual language was brought to America from Germany by Carl Laemmle (founder of Universal Studios in 1912) and his son Carl Laemmle, Jr. (in charge of production from 1928-36).

There are those who criticize the plots, character development, dialogue, and acting in these 1930s’ movies. Yet it is the power of the visual images that captured me as an adolescent viewer and has stayed with me today as a more sophisticated and image-conscious art historian. This new visual language was brought to America from Germany by Carl Laemmle (founder of Universal Studios in 1912) and his son Carl Laemmle, Jr. (in charge of production from 1928-36).

Born in Germany in 1867, Carl Sr. immigrated to the United States in 1884. His interest and expertise in the rich traditions of German filmmaking are seen in Universal’s landmark silent films featuring Lon Chaney Sr.: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Carl Jr. continued his father’s legacy at the studio becoming the guiding force behind the iconic Universal horror films.

Born in Germany in 1867, Carl Sr. immigrated to the United States in 1884. His interest and expertise in the rich traditions of German filmmaking are seen in Universal’s landmark silent films featuring Lon Chaney Sr.: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Carl Jr. continued his father’s legacy at the studio becoming the guiding force behind the iconic Universal horror films.

The strength and staying power of the Universal horror films resonate through the remarkable visual achievements in lighting, sets, make-up, and costumes. This unique Universal “look” was created by the cinematography of Arthur Edeson, Karl Freund, Paul Ivano, George Robinson, and Joseph Valentine; make-up designs by Jack Pierce; set designs by Kenneth Strickfaden; and costume designs by Vera West. The images carried the weight of the stories and those images imprint themselves and remain in the mind’s eye of the viewer long after their original narrative context is lost or forgotten. The visual worlds created on screen made a profound and lasting impression on me.

The strength and staying power of the Universal horror films resonate through the remarkable visual achievements in lighting, sets, make-up, and costumes. This unique Universal “look” was created by the cinematography of Arthur Edeson, Karl Freund, Paul Ivano, George Robinson, and Joseph Valentine; make-up designs by Jack Pierce; set designs by Kenneth Strickfaden; and costume designs by Vera West. The images carried the weight of the stories and those images imprint themselves and remain in the mind’s eye of the viewer long after their original narrative context is lost or forgotten. The visual worlds created on screen made a profound and lasting impression on me.

These worlds were full of places and people and events that were strange, mysterious, hypnotic, exotic, and yet somehow relevant to me. I couldn’t explain my feelings but I recognized them. My own first attempts at writing short stories revolved around the personalities and scenes from these films. I sat at my kitchen table while my mother washed dishes and invented tales about burgomasters, abandoned castles, and monsters. My first attempts at film “analysis” (I guess you might say my first film lectures) were delivered to my friends (especially to those whose parents did not allow them to stay up late on Saturday nights) about monster movies. And I cast and directed my own versions of the stories, reenacting crucial moments, the three major roles being the Frankenstein monster (my role), Dracula, and the Wolf Man (the roles always played by my two closest friends).

These worlds were full of places and people and events that were strange, mysterious, hypnotic, exotic, and yet somehow relevant to me. I couldn’t explain my feelings but I recognized them. My own first attempts at writing short stories revolved around the personalities and scenes from these films. I sat at my kitchen table while my mother washed dishes and invented tales about burgomasters, abandoned castles, and monsters. My first attempts at film “analysis” (I guess you might say my first film lectures) were delivered to my friends (especially to those whose parents did not allow them to stay up late on Saturday nights) about monster movies. And I cast and directed my own versions of the stories, reenacting crucial moments, the three major roles being the Frankenstein monster (my role), Dracula, and the Wolf Man (the roles always played by my two closest friends).

A final element at work in these films -- often present in any film from the distant past had to do with their age and condition as I first viewed them on television. The small screen, the muffled soundtracks, disruptive jumps, lighting inconsistencies, and the slowly decaying film stock imbued each movie with a patina of audio and visual textures beyond its original cinematic intention.

A final element at work in these films -- often present in any film from the distant past had to do with their age and condition as I first viewed them on television. The small screen, the muffled soundtracks, disruptive jumps, lighting inconsistencies, and the slowly decaying film stock imbued each movie with a patina of audio and visual textures beyond its original cinematic intention.

I am an advocate and supporter of all efforts at film preservation but something beautiful, familiar, and meaningful emerged through those worn and fatigued images – something that continues to speak today to my own organic and synchronous aging process. It is as if we have been partners on an extraordinary journey. As a young boy the films’ characters and stories mattered very much to me. But it is the fragility of the film record itself, re-contextualized, re-examined, and re-viewed against the shifting events of my life that remains most deeply embedded in me. The films are both the same and yet different; just as I am.

I am an advocate and supporter of all efforts at film preservation but something beautiful, familiar, and meaningful emerged through those worn and fatigued images – something that continues to speak today to my own organic and synchronous aging process. It is as if we have been partners on an extraordinary journey. As a young boy the films’ characters and stories mattered very much to me. But it is the fragility of the film record itself, re-contextualized, re-examined, and re-viewed against the shifting events of my life that remains most deeply embedded in me. The films are both the same and yet different; just as I am.

A great moment in horror films, as the sinister yet suave Count Dracula, played by Bela Lugosi, confronts the weary but shrewd Professor Van Helsing, played by Edward Van Sloan, in one of Universal Studios best “monster movies.” What is it about those Universal horror films of the ‘30s and ‘40s that I first saw on television as a young boy growing up in Rochester, New York in the ‘50s and ‘60s, which still resonates with me today? Why are films like Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and The Wolf Man (1941) so indelibly stamped into my psyche that now, years later, I still get feelings of exhilaration, nostalgia, and a strange comfort whenever I watch them? Everything about those films, from their opening music and credits announcing "The Players," to the moody and rich play of light and shadow (blacks and whites) and exaggerated expressionist sets, speaks to a sensibility deep inside me.

On the surface, and compared to horror films today, films like Dracula and Frankenstein appear dated, bloodless (in both the literal and figurative senses of the word), tame, sometimes comical, and maybe even a bit sweet. But embedded in the deeper recesses of the films' smart scripts, talented casts, sharp direction (especially by James Whale), and atmospheric effects are cinematic and human qualities hard to describe and even harder to explain. There is something dignified and poignant about the stories, the plights of the main characters (notably the monsters) and their responses to events, reactions to injustices and to a world around them that is hostile,cruel, and senseless. That is a key element – the films encourage us to identify with the monsters and not with the protagonists who attempt to maintain the order and structures of society. It is one reason why the films are so powerful, resonant, even mythic.

On the surface, and compared to horror films today, films like Dracula and Frankenstein appear dated, bloodless (in both the literal and figurative senses of the word), tame, sometimes comical, and maybe even a bit sweet. But embedded in the deeper recesses of the films' smart scripts, talented casts, sharp direction (especially by James Whale), and atmospheric effects are cinematic and human qualities hard to describe and even harder to explain. There is something dignified and poignant about the stories, the plights of the main characters (notably the monsters) and their responses to events, reactions to injustices and to a world around them that is hostile,cruel, and senseless. That is a key element – the films encourage us to identify with the monsters and not with the protagonists who attempt to maintain the order and structures of society. It is one reason why the films are so powerful, resonant, even mythic.

The humanity of these films is realized and conveyed in no small way through the performances of the serious actors who overcame whatever misgivings they may initially have had about impersonating a lowly monster to embrace and explore the complexities and subtleties of the tortured souls their characters represent. Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, and Lon Chaney Jr. commit themselves to the sincerity of their respective creatures; creatures experiencing all the torment and frustration of lives lived in a world beyond their control.

The humanity of these films is realized and conveyed in no small way through the performances of the serious actors who overcame whatever misgivings they may initially have had about impersonating a lowly monster to embrace and explore the complexities and subtleties of the tortured souls their characters represent. Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, and Lon Chaney Jr. commit themselves to the sincerity of their respective creatures; creatures experiencing all the torment and frustration of lives lived in a world beyond their control.

Even as a child I recognized the conflicts these characters faced. In fact, it wasn’t so much the horror effects of these films that moved me (I

Even as a child I recognized the conflicts these characters faced. In fact, it wasn’t so much the horror effects of these films that moved me (I

David Gariff is a senior lecturer at the National Gallery of Art. A specialist in modern and contemporary art and the art of the Italian Renaissance, he has taught art and film history at the University of Wisconsin, Cleveland State University, Trinity University, and the University of Maryland. David has lectured and written widely on topics related to modern art, film, and the Italian Renaissance. His book The World’s Most Influential Painters and the Artists They Inspired explores the theme of artistic influence and inspiration in Western painting. His film notes from the National Gallery of Art can be found at: www.nga.gov/Programs and Events/Film Programs/Film Program Archive.

can't remember actually feeling frightened by what I saw) as it was their psychological dimension. Here were bad things happening to good people, noble intentions suffering at the hands of ambition and hubris, lack of communication and misunderstandings between and among people, monsters, perpetrators and victims; and finally, basic challenges to my as yet unformed attitudes regarding nature, science, religion, reason, superstition, good and evil, myth and legend, the real and the imagined.

The trouble with truth is that it just doesn't get out much...

New York City is obsessed with food. Especially in the streets of The Quarter, every imaginable delicacy is made and devoured, every unspeakable hunger is fulfilled.

Talia, a recent divorcee, comes to The Quarter to be reborn. She discovers fresh purpose in the sensual pleasures there, and a possible new love. But eventually she finds herself face to face with the darkness under its surface—in both the privileged patrons who feast there, and the third-world laborers who feed them.

Now Talia must separate the truth from the madness because in The Quarter, the haves and have-nots are about to face a reckoning.